Throughout history, women have played a vital role in shaping healthcare, pioneering medical breakthroughs, and advocating for better wellness solutions. This page honors the women who have made lasting contributions to medicine, healthcare, and the well-being of women everywhere. Each month, we highlight a remarkable woman in our email newsletter, celebrating her impact and legacy.

Historically, the realm of surgery was largely considered a male domain, with women facing considerable discouragement and outright prevention from entering the field. Despite these formidable barriers, numerous women exhibited extraordinary courage and skill, making groundbreaking contributions to surgical practices throughout history.

One of the earliest known figures is Metrodora, a female Greek physician who lived between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE. Her treatise, “On the Diseases and Cures of Women,” stands as the oldest known medical text authored by a woman. Within its pages, Metrodora detailed pioneering surgical treatments for conditions like breast and uterine cancers. Her work demonstrates that women have possessed and disseminated surgical knowledge for millennia, a fact that challenges the conventional narrative of surgery as a field exclusively dominated by men from its inception.

If you know someone whose story deserves to be shared, we invite you to nominate her using the form below.

Table of Contents

Dr. Mary-Claire King

Honored Geneticist

Geneticist Who Uncovered the Breast Cancer Gene

Brief Biography: Dr. Mary-Claire King is an American geneticist whose research revolutionized understanding of hereditary breast cancer, saving the lives of countless women. Born in 1946, King earned her Ph.D. in genetics from UC Berkeley in 1973. Early in her career, she made a startling finding that humans and chimpanzees share 99% of their DNA, illustrating the power of genetics to answer big questions. In the 1970s and 80s, as a professor, King turned her focus to a question that was highly controversial at the time: could breast cancer be passed down in families due to a gene mutation? For 17 years she painstakingly gathered epidemiological data and genetic evidence from breast cancer patients and families. In 1990, Dr. King made a landmark discovery: she proved the existence of a particular gene on chromosome 17 whose mutations greatly increase the risk of breast cancer in women. This breakthrough fundamentally changed cancer research and care.

Key Contributions: Dr. King is best known for the discovery of the BRCA1 gene (identified by her team in 1990 as the first gene responsible for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer). She demonstrated that certain mutations in BRCA1 confer an extraordinarily high lifetime risk (up to ~80%) of breast cancer in women, explaining why some families were plagued by the disease. This finding led to genetic tests that can identify women carrying BRCA mutations. As a direct result, women who test positive can take preventive measures (such as enhanced screening or prophylactic surgery) to dramatically reduce their cancer risk, a practice Dr. King herself has advocated to “save women’s lives.” King’s work didn’t stop with BRCA1 – it opened the door to discovering a second breast cancer gene, BRCA2 in 1995 and a deeper understanding that inherited genetic errors can drive cancer. Beyond cancer, Dr. King has applied genetic tools to human rights: in the 1980s, she pioneered the use of DNA to identify missing persons (such as children of victims of Argentina’s “Dirty War”), reuniting families through science. While this humanitarian work is outside women’s health, it underscores her broad impact as a scientist.

Major Recognitions: Mary-Claire King’s contributions have earned her the highest honors in science. In 2016 she received the National Medal of Science, the United States’ top scientific honor, for her genetics research. Two years earlier, she won the 2014 Lasker~Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science, often called “America’s Nobels,” for her discovery of BRCA1 and her advocacy in applying genetics to benefit society. Dr. King is an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences (since 2005) and National Academy of Medicine. In 2021, she received the Canada Gairdner International Award, and in 2025 the National Academy of Sciences awarded her the Public Welfare Medal for her contributions to science in service of the public. These are among dozens of accolades, including the Shaw Prize, the Albany Medical Center Prize, and multiple honorary doctorates. She was also Glamour’s “Woman of the Year” in 1993 and has been recognized by the Susan G. Komen foundation for her impact on breast cancer research.

Lasting Influence: Dr. King’s work has had a transformative and lasting impact on women’s physical health. Thanks to her discovery of BRCA1, genetic screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk has become standard practice – empowering women with knowledge about their health. Countless lives have been saved or extended by preventive actions taken by BRCA-positive women (from increased surveillance to prophylactic mastectomies or oophorectomies). King’s insistence that breast cancer can be inherited fundamentally changed medical thinking; today, family history is a key component of cancer risk assessment, and research into genetic causes of cancer is mainstream. Furthermore, her model of using genetics for disease prevention has influenced public health: programs now identify individuals at high risk for various cancers or disorders through genetic counseling and testing, allowing early interventions. As a trailblazing female scientist, King has also inspired generations of women to enter biomedical research and genetics. She continues to be active in research and advocacy, emphasizing that widespread genetic screening and accessible testing are crucial so that “women’s lives can be saved” by preventive care. In summary, Mary-Claire King’s legacy lies in proving that understanding our genes can empower us to improve health outcomes – a principle now integral to women’s healthcare and precision medicine.

Dr. Patricia Bath

A Visionary Pioneer in Eye Health

Dr. Patricia Bath was a groundbreaking ophthalmologist, inventor, and humanitarian whose relentless dedication transformed eye care, especially for underserved communities. Her journey, marked by perseverance and an unwavering commitment to health equity, is an inspiring testament to the power of medical science and innovation.

Born in Harlem, New York, Dr. Bath’s brilliance was evident from an early age. Her pursuit of knowledge led her to Hunter College, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in chemistry in 1964. This strong foundation in science propelled her to Howard University College of Medicine, where she received her medical degree in 1968.

Throughout her medical training, Dr. Bath was acutely aware of stark disparities in healthcare. During her internship at Harlem Hospital and a subsequent ophthalmology fellowship at Columbia University, she observed a significantly higher prevalence of blindness and visual impairment among African American patients compared to white patients. This stark reality fueled her lifelong mission: to ensure that “eyesight is a basic human right” for all.

Driven by this conviction, Dr. Bath pioneered the field of Community Ophthalmology. This innovative discipline combined public health, community medicine, and clinical practice to bring essential eye care services to underserved populations. She established programs that provided screenings and treatments, preventing blindness in thousands who would otherwise have gone undiagnosed.

Her most revolutionary contribution came with the invention of the Laserphaco Probe in 1986. This groundbreaking device revolutionized cataract surgery, making it less invasive, more precise, and highly effective. With this invention, Dr. Bath became the first African American female physician to receive a medical patent. The Laserphaco Probe has since restored sight to countless individuals globally, cementing her legacy as a true medical luminary.

Dr. Patricia Bath’s life and career stand as a powerful reminder of how one individual’s education, scientific curiosity, and deep commitment to social justice can profoundly impact global health and pave the way for future generations in medicine.

Dr. Antonia Novello

Dr. Antonia Novello, the 14th U.S. Surgeon General, was a trailblazer in public health, particularly in advancing women’s health. Appointed in 1990, she was the first woman and first Hispanic to hold the position. Her tenure was marked by initiatives targeting health disparities affecting women, children, and minorities.naaonline.orgnaaonline.org+2Wikipedia+2Hopkins Medicine+2

One of her significant contributions was raising awareness about AIDS among women and the neonatal transmission of HIV. She was among the first health officials to highlight these issues, leading to increased attention and resources for affected populations. Alliance for Early Success+4Hooper Lundy & Bookman+4Specialty Care US+4

Dr. Novello also focused on domestic violence, bringing national attention to its impact on women’s health. She worked to elevate public consciousness about the issue, advocating for better support systems for victims. womenofthehall.org

Her efforts extended to combating underage drinking and smoking, particularly targeting advertising practices that appealed to youth. She criticized the use of cartoon characters like “Joe Camel” in tobacco advertising, leading to changes in marketing strategies. OHSUWikipedia+1Hooper Lundy & Bookman+1

Beyond her role as Surgeon General, Dr. Novello served as a special representative for UNICEF, focusing on the health and nutritional needs of women, children, and adolescents globally. Her lifelong commitment to public health has left a lasting impact on healthcare policies and practices concerning women’s health.Wikipedia+10cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov+10National Women’s History Museum+10

Dr. Edith Mitchell

Posted in December 2024:

Dr. Edith Peterson Mitchell (1947-2024) was a pioneering oncologist and retired Air Force Brigadier General who dedicated her career to improving healthcare access and outcomes, particularly for underserved communities.

Key medical and health contributions:

- Served as clinical professor of medicine and medical oncology at Thomas Jefferson University

- Became president of the National Medical Association in 2015

- Established the Center to Eliminate Cancer Disparities at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center

- Conducted significant research on pancreatic and colorectal cancers, including new drug evaluation, chemotherapy regimens, and patient selection criteria

- Led the NRG Oncology/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group in establishing clinical evidence for combined-modality cancer treatments

- Served on Vice President Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot Initiative panel

- Created patient education videos about cancer screening and treatment that were distributed nationwide

- Responded to public health emergencies, including leading a team to combat flooding in Missouri and Mississippi in 1993, helping provide safe drinking water and administer hepatitis vaccines

Her work earned numerous recognitions, including the American Cancer Society Cancer Control Award, CancerCare’s Physician of the Year, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology Humanitarian Award. Throughout her career, she remained committed to addressing healthcare disparities and improving care quality for all patients, influenced by her own experiences growing up during racial segregation with limited access to quality healthcare.

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens

Posted in January 2025

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens (1909–2001) earned her medical degree (M.D.) from the University of Illinois College of Medicine in 1934 and made significant contributions to medicine and public health throughout her career. She was a pioneering physician, health advocate, and educator who made groundbreaking contributions to the fields of obstetrics, gynecology, and public health. In 1950, she became the first African-American woman admitted to the American College of Surgeons. Throughout her career, she championed equitable healthcare for underserved communities and addressed critical issues like teen pregnancy, cervical cancer prevention, and racial disparities in medicine.

Dickens founded the Teen Clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, offering comprehensive support for young mothers, and significantly increased minority admissions during her tenure as dean for minority admissions at Penn. Her extensive research on teen pregnancy and cancer detection, including early adoption of pap tests, earned her widespread recognition, including the Gimbel Philadelphia Award and the Sadie Alexander Award.

Helen Octavia Dickens was the daughter of a former enslaved man who emphasized the transformative power of education, a value she carried throughout her life and career.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

Posted in March 2025

In the annals of medical history, few figures shine as brightly as Rebecca Lee Crumpler, a trailblazer whose contributions reverberate through time. Born on February 8, 1831, in Christiana, Delaware, Crumpler overcame immense societal barriers to become the first African-American woman to earn a medical degree in the United States in 1864. Her journey—from a young girl inspired by her aunt’s care for the sick to a pioneering physician, author, and advocate—offers a profound testament to resilience, compassion, and the pursuit of knowledge. Her work not only advanced maternal and pediatric care but also laid the groundwork for future generations of women and African Americans in medicine.

Crumpler’s path to medicine was unconventional yet purposeful. Raised in Pennsylvania by an aunt who served as a community healer, she developed an early passion for alleviating suffering. This led her to nursing in the 1850s, a role she pursued for eight years before gaining admission to the New England Female Medical College. Graduating in 1864, at a time when neither women nor African Americans were widely accepted in medical education, she broke new ground. Her career unfolded against the backdrop of the Civil War and its aftermath, where she dedicated herself to caring for the underserved—particularly poor women, children, and newly freed enslaved people.

“I early conceived a liking for and sought every opportunity to relieve the suffering of others.” -Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

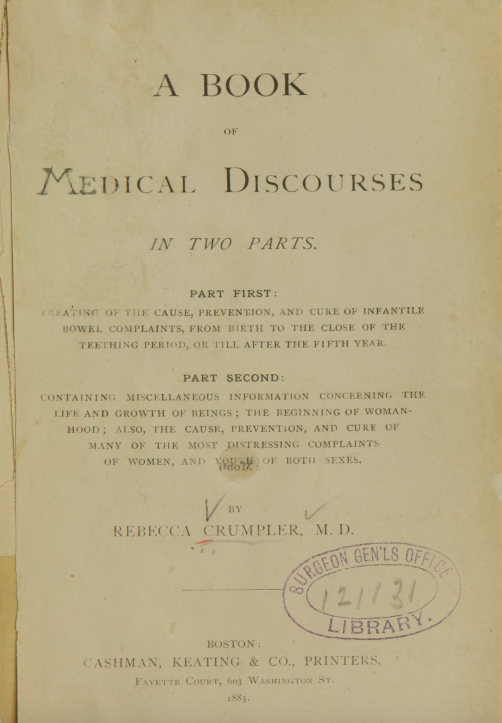

One of Crumpler’s most enduring contributions came in 1883 with the publication of A Book of Medical Discourses. Dedicated to nurses and mothers, this two-part work focused on maternal and pediatric health, offering practical advice on preventing and treating childhood illnesses and supporting human growth. As one of the first medical texts authored by an African American, it stands as a pioneering effort to democratize medical knowledge. Crumpler’s emphasis on prevention underscored her belief that understanding the causes of ailments empowered caregivers to protect life—a radical idea in an era dominated by reactive treatments.

Her practical impact was equally significant. In Boston, she treated impoverished African-American women and children, often without regard for their ability to pay. After the Civil War, she moved to Richmond, Virginia, working with the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide medical care to freedmen and freedwomen denied services by white physicians. Facing intense racism and sexism—male doctors sometimes dismissed her credentials or refused to fill her prescriptions—she persevered, driven by a missionary zeal to serve. Later, returning to Boston’s Beacon Hill, she continued her practice, leaving a legacy honored today by stops on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail and societies named in her honor.

- Fascinating Facts About Rebecca Lee Crumpler:

- First of Her Kind: In 1864, Crumpler became the first African-American woman to earn an MD in the U.S., predating others previously credited with the milestone.

- Literary Pioneer: Her 1883 book, A Book of Medical Discourses, was among the earliest medical publications by an African American, blending medical advice with personal insights.

- Civil War Service: She worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau post-war, treating thousands in Richmond despite hostility from peers who mocked her M.D. as “Mule Driver.”

- Educational Rarity: She was the only African-American student at the New England Female Medical College during her time there, graduating amidst a predominantly white, male medical world.

- Unnamed Graves No More: After 125 years in unmarked graves, Crumpler and her husband Arthur received headstones in 2020, thanks to a community fundraising effort.

Crumpler’s influence extends beyond her lifetime. The Rebecca Lee Society, one of the first medical societies for African-American women, and Syracuse University’s Rebecca Lee Pre-Health Society bear her name, inspiring diverse students to enter healthcare. Official recognitions, like Virginia’s Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler Day on March 30 and Boston’s commemoration on February 8, affirm her lasting impact. Her story is a beacon for those navigating systemic barriers, proving that dedication and skill can reshape history.

Rebecca Lee Crumpler’s life was a quiet revolution. Through her practice, her writing, and her unwavering commitment to the marginalized, she not only healed bodies but also challenged the prejudices of her era. As we reflect on her contributions, we’re reminded that progress in health and equity often begins with the courage of individuals like her—those who dare to care, learn, and lead when the odds are stacked against them.

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

Posted in April 2025

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865-1915) was a trailblazing physician and reformer, widely recognized as the first Indigenous woman in the United States to earn a medical degree.

Born in 1865 on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska, Picotte’s commitment to health and healing was inspired early in life after witnessing the death of a Native woman who had been denied care by a white physician. Determined to change this reality for her people, she pursued an education that defied the expectations of both gender and race at the time.

Picotte’s academic journey began at the mission school on the Omaha Reservation, followed by advanced studies at the Elizabeth Institute in New Jersey and the Hampton Institute in Virginia. Her intellectual dedication was evident from a young age—graduating as salutatorian from Hampton and receiving the Demorest Prize for academic excellence.

In 1886, she applied to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, one of the few institutions that admitted women, where she studied subjects ranging from chemistry and physiology to obstetrics and general medicine.

With financial support from the Connecticut Indian Association, Picotte completed her rigorous three-year medical program and graduated as valedictorian in 1889. Her education was not merely academic—it was deeply mission-driven. She intended to return to her community not only to treat illnesses but to teach hygiene and preventive health practices, bridging Western medical knowledge with the cultural and practical needs of the Omaha people.

Upon returning to the Omaha Reservation, Dr. Picotte became the physician at the government boarding school and soon expanded her care to the broader community. She often worked 20-hour days, serving more than 1,200 patients across a 450-square-mile area. Her medical practice encompassed treatment of illnesses like tuberculosis, trachoma, cholera, and influenza, while also addressing everyday needs such as writing letters or navigating government paperwork. She was both a healer and a vital advocate for community well-being.

Beyond clinical care, Dr. Picotte led groundbreaking public health initiatives. She campaigned against alcohol consumption, spearheaded sanitation education, and championed disease prevention—particularly against tuberculosis, which tragically claimed her husband’s life. She worked tirelessly to educate the public on hygiene and school health and chaired the Nebraska Federation of Women’s Clubs’ state health committee. In 1913, her advocacy culminated in the opening of a reservation hospital, the first of its kind privately funded on Native land.

Dr. Picotte’s impact extended into medical and legal reform. She navigated complex bureaucracies to secure land and inheritance rights for herself and others in the Omaha community. As a trusted leader, she advocated for better management of Native affairs, exposed systemic fraud, and defended tribal autonomy. Her work exemplified a holistic approach to health—addressing not only physical ailments but the structural and social determinants of wellness.

Her legacy endures not only through the hospital bearing her name but in the broader history of American medicine and Indigenous advocacy. Through her pioneering efforts, Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte transformed what was possible for Native women in medicine and left a lasting imprint on public health practices in underserved communities. Her story continues to inspire generations of health professionals committed to care, equity, and justice.

Rosalind Franklin

Author: MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Posted For May 2025

The Unsung Heroine Who Revolutionized Women’s Health. Rosalind Franklin’s (July 1920 – April 1958) contributions to the discovery of the DNA double helix through X-ray crystallography were pivotal, though often not fully acknowledged during her lifetime. Her work provided critical insights into the structure of DNA, laying the groundwork for modern genetics and molecular biology, fields that are fundamental to our understanding and treatment of a vast array of diseases. Her story serves as a reminder of the importance of recognizing the contributions of all scientists, regardless of gender, and her legacy continues to inspire women in scientific research and medicine.

Rosalind Franklin’s name is often eclipsed by the towering legacies of Watson and Crick, but her pioneering work in molecular biology and virology fundamentally transformed modern medicine—particularly in safeguarding and advancing women’s health. A master of precision and innovation, Franklin’s contributions bridged the gap between abstract science and life-saving medical breakthroughs, leaving a legacy that continues to empower women globally.

Decoding DNA: A Blueprint for Women’s Health

Franklin’s iconic Photo 51, an X-ray diffraction image of DNA, revealed the molecule’s double-helix structure with startling clarity. While her male peers used her data without acknowledgment, the discovery became the cornerstone of genetics. For women, this breakthrough was transformative: it unlocked the ability to study hereditary diseases linked to DNA mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which dramatically increase risks of breast and ovarian cancers.

Franklin’s work laid the groundwork for genetic screening, enabling early detection and personalized treatment plans. Today, millions of women benefit from prenatal testing, cancer risk assessments, and therapies tailored to their genetic profiles—advancements rooted in her meticulous research. Her insistence on precision in X-ray crystallography set a gold standard, ensuring future discoveries would be built on reliable, reproducible science.

Viruses, Vaccines, and Saving Lives

After DNA, Franklin turned her genius to viruses. Her 3D mapping of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV)exposed how viral RNA hijacks host cells—a revelation that reshaped virology. This work directly informed her later analysis of the polio virus during the 1950s epidemic, a crisis that disproportionately threatened mothers and children. By deciphering the virus’s structure, she provided critical insights into how it spread and replicated, data that became instrumental in developing Jonas Salk’s and Albert Sabin’s vaccines.

Polio’s decline didn’t just save lives; it preserved futures. Women, often primary caregivers, faced immense physical and emotional strain when polio struck families. Vaccines freed communities from outbreaks that could paralyze children and overwhelm healthcare systems. Franklin’s work also pioneered techniques later used to study HPV (human papillomavirus), a leading cause of cervical cancer. Today, HPV vaccines—direct descendants of her methodologies—prevent thousands of cancer cases annually, offering women a shield against a once-untreatable disease.

Radiation, Risk, and a Life Cut Short

Franklin’s dedication came at a cost. Her relentless exposure to X-ray radiation, a hazard of pre-safety-regulation labs, likely contributed to her ovarian cancer diagnosis at age 37. She continued working until weeks before her death in 1958, publishing 13 papers in her final two years. Tragically, her early passing meant she never saw the full impact of her work—or received the accolades she deserved.

Legacy: A Foundation for Future Generations

Franklin’s influence extends far beyond her lifetime. Her X-ray techniques became essential tools for studying pathogens like Zika and HIV, viruses that pose unique risks to women’s reproductive and immune health. Modern breast cancer therapies, including targeted drugs like Herceptin, rely on understanding DNA-protein interactions she helped elucidate.

Yet her greatest legacy may be symbolic. Franklin thrived in a male-dominated field, her achievements often dismissed or appropriated. Today, she inspires women in STEM to demand recognition and resources. Organizations like Rosalind Franklin University and scholarships in her name champion gender equity in science, ensuring her story reshapes the future as profoundly as her research reshaped medicine.

Visibility Saves Lives

Rosalind Franklin’s story is a testament to how foundational science becomes lifelines for marginalized communities. By illuminating the invisible—DNA, viruses, molecular structures—she gave medicine the tools to protect women’s bodies and futures. Her life underscores a urgent truth: when women’s contributions are erased, progress falters. Honoring her legacy means advocating for equity in labs, clinics, and classrooms—because the next Rosalind Franklin could hold the key to ending the diseases that still plague women worldwide.

In a world quick to overlook women’s brilliance, Franklin’s work reminds us: seeing the unseen changes everything.